During the height of Modernism’, a group of writers surfaced, zeroing in on the cultural, scientific, and socio-economic issues plaguing Spain.

This cohort, known as the Generation of ‘98, didn’t diverge from Modernism nor contest it. Instead, they were authors bound by contemporary aesthetic ideas, collectively devoted to tackling Spain’s adversities and scrutinizing the nation’s state with a critical lens.

The Generation Of ‘98

Themes

The Group of ‘98 looked at two main areas:

Spain’s Challenges. They explored what makes Spain unique by looking at its land, people, history, and classic writings. The writers had mixed feelings: they pointed out issues like poverty and neglect but also praised Spain’s natural beauty and the spirit of its people.

Deep Thoughts on Life. They thought deeply about big life questions like the meaning of life, death, loneliness, and changes in moral values during their time. This led them to express feelings of sadness, doubt, and tiredness in their works, reminiscent of the romantic era but with a modern twist.

The Style

The ‘98 writers embraced new ways of Modernist writing but steered clear of too much fancy talk. They preferred clear and straightforward language, yet put a lot of thought into choosing their words, often picking ones with traditional flavor.

They wrote with deep feeling and a personal touch, making their writing lyrically beautiful. They sometimes aimed to share exactly what they felt and saw, and at other times, they used bold and vivid language to sharply critique Spain’s problems.

They worked across all forms of writing - like poems, stories, and plays. Yet, their thoughtful and critical approach made essays and prose particularly fitting for their ideas.

Members of the Generation of ‘98

Even though these writers focused on similar issues at times, each had a unique style and set of beliefs. They went in different directions with their work: Baroja valued independence, while Antonio Machado was known for his dedication. Azorín leaned towards conservative views, in contrast to Valle-Inclán’s forward-thinking ideas.

Azorín

Pseudonym of José Martínez Ruiz (1873-1967). Essayist. He was actively involved in politics during the early years of his career.

The dominant theme of his writings is the theme of Spain and eternity and continuity, symbolized in the ancestral customs of the peasants. He gained critical recognition for his essays, among which stand out El alma castellana (1900), Los pueblos (1904), and Castilla (1912). He is best known for his autobiographical novels La Voluntad (1902), Antonio Azorín (1903), and Las confesiones de un pequeño filósofo (1904). Azorín introduced a new and vigorous style into Spanish prose.

His work also stands out for the astute literary criticism he performs in texts such as Los valores literarios (1913) and Al margen de lo clásico (1915). He was the leading representative of this generation.

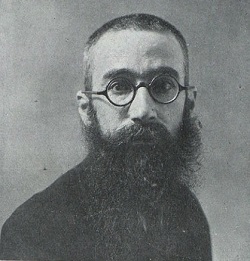

Unamuno

He is considered the most intellectual writer of ‘98.

Born in Bilbao, Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo (1864-1936) studied at the University of Madrid, where he obtained his doctorate in Philosophy and Letters. He was a professor of Greek at the University of Salamanca from 1891 until 1901, when he was appointed rector.

His philosophy, which was not systematic, permeates all his production. Intellectually formed in rationalism and positivism, in his youth he sympathized with socialism, writing several articles for the newspaper El socialista, where he showed his concern for the situation in Spain. This concern for Spain is manifested in his essays collected in his books En torno al casticismo (1895), Vida de Don Quijote y Sancho (1905), and Por tierras de Portugal y España (1911). Poems dedicated to exalting the lands of Castile are also frequent.

He cultivated all literary genres: he was a poet, novelist, playwright, and literary critic. His narrative begins with Paz en la guerra (1897), continues with Niebla (1914), La tía Tula, and San Manuel bueno, mártir (both from 1933).

Among his poetic work, El Cristo de Velázquez (1920) stands out, while his theater has had less success.

Pío Baroja

Pío Baroja (1872-1956) is the great novelist of the group. He was born in San Sebastián (Basque Country) and studied Medicine in Madrid, the city where he lived most of his life.

His first novel was Vidas sombrías (1900), followed that same year by La casa de Aizgorri. This novel is part of the first of Baroja’s trilogies, Tierra vasca, which also includes El mayorazgo de Labraz (1903), and Zalacaín el aventurero (1909). In 1911 he published El árbol de la ciencia. Between 1913 and 1935, the 22 volumes of a historical novel, Memorias de un hombre de acción, appeared. Between 1944 and 1948, his Memoirs were published, of utmost interest for the study of his life and work.

His novels are full of incidents and very well-drawn characters, and stand out for the fluidity of their dialogues and impressionist descriptions. Master of the realistic portrait, he has an abrupt, vivid, and impersonal style.

Antonio Machado

Antonio Machado (1875-1939). He is another one of the greatest and most famous Spanish poets.

He was born in Seville and later lived in Madrid, where he studied. In 1893 he published his first writings in prose, while his first poems appeared in 1901. He was a professor of French, and married Leonor Izquierdo. In 1927 he was elected member of the Royal Spanish Academy.

During the twenties and thirties, he wrote theater in collaboration with his brother, premiering several plays among which stand out La Lola se va a los puestos (1929) and La duquesa de Benamejí (1931). In January 1939, he went into exile in the French town of Collioure, where he died in February.

His first book is Soledades (1903), modernist poems, in which the emotion of the moment and the hidden meaning of what surrounds him stand out. Campos de Castilla (1912), a poetic consideration of the Castilian landscape, along with the emotion of lost love. In 1917 Páginas escogidas were published, and the first edition of Poesías completas. From that time remains an important work in prose, Los complementarios, which constitutes a set of impressions, reflections about the everyday and sketches. Nuevas canciones (1914) continues the sententious and philosophical line where social criticism increasingly stands out, without losing the lyrical resonance. In 1936 he published a prose book, Juan de Mairena. Sentences, jokes, notes and memories of an apocryphal professor. The Civil War prompted him to write poems of a circumstantial and political type.

Valle-Inclán

Ramón María del Valle-Inclán (1866-1936), was a Spanish novelist, poet, and playwright, as well as short story writer, essayist, and journalist.

He was born in Villanueva de Arosa, Pontevedra, and studied law in Santiago de Compostela, but interrupted his studies to travel to Mexico, where he worked as a journalist. In 1931 he held several official positions, including that of Director of the School of Fine Arts in Rome. He later returned to Galicia where he died in January 1936, in Santiago de Compostela.

His first book was Femeninas (1895), followed by works inspired by Galician themes, where the lyrical stylization of the rural and popular atmosphere stands out, such as Flor de Santidad (1904), the poetry of Aromas de leyenda (1907). That same year he married Josefina Blanco, and published the first of his so-called barbaric comedies, Águila de blasón, followed by Romance de lobos (1908), works of great dramatic stylization in a violent environment with medieval resonances. In Cara de plata (1922), the third volume of this theatrical trilogy, the turn towards considerations of social criticism is again observed.

His second trip to Mexico probably inspired the writing of Tirano Banderas (1926), considered his best novel.

Luces de bohemia, his theatrical work from 1920, established an aesthetic of deformation, through which he stylizes the low, the ugly, with a kind of gestural and caricatural expressionism.

Valle-Inclán returned to write historical novel in El ruedo ibérico, a series of novels based on the reign of Isabel II, which shows a bitter satirical vision of Spanish reality, and consists of La corte de los milagros (1927), Viva mi dueño (1928) and Baza de espadas.

The Generation of ‘98 represents a unique and pivotal moment in Spanish literature, marked by a collective response to national crises through a blend of modern aesthetic innovation and deep cultural introspection. These authors, despite their diverse viewpoints and individual paths, were united by a common goal: to explore, critique, and ultimately enrich the understanding of Spain’s identity and challenges.

Their legacy teaches us the power of literature not just to reflect societal issues, but to inspire reflection, debate, and growth. The Generation of ‘98 reminds us that in times of turmoil, art and literature become vital instruments for examining the past, understanding the present, and imagining the future.

Read also: Literary Modernism in Latin America