Esperanto: The Language That Refuses to Die (and Why You Should Care)

Most people think Esperanto is a weird nerd project from the 1800s that went nowhere. Wrong!

Esperanto is alive, kicking, and spoken by hundreds of thousands (some say millions) across the globe. It’s been used in classrooms, international congresses, on Duolingo, and even in Vatican Radio broadcasts. And if you’re curious about languages, world peace, or just want a linguistic superpower in your back pocket, you should pay attention.

Esperanto’s Origin Story: A Doctor With a Dream

The year is 1887. A Polish-Jewish ophthalmologist named L. L. Zamenhof publishes a little green book called Unua Libro under the pen name “Dr. Esperanto,” meaning one who hopes¹.

He grew up in Białystok, a city full of Poles, Jews, Russians, and Germans who didn’t exactly get along. Zamenhof thought: What if everyone had a second language in common? A neutral one. Simple, logical, and not tied to any empire. Then Esperanto was born.

And the crazy thing? The community stuck. From day one, people started writing, speaking, and meeting in Esperanto. By 1905 there was already a World Congress of Esperanto in France with thousands attending².

What Language Is Esperanto, Anyway?

Here’s the quick definition:

Esperanto is a constructed language. It was designed for one purpose: to be easy to learn and totally neutral.

So what makes it different? Let me show you:

- Grammar with no exceptions.

Forget irregular verbs. In Esperanto, everything is predictable.

Example:- mi estas = I am

- vi estas = you are

- ili estas = they are

That’s it. No “am/are/is” nonsense.

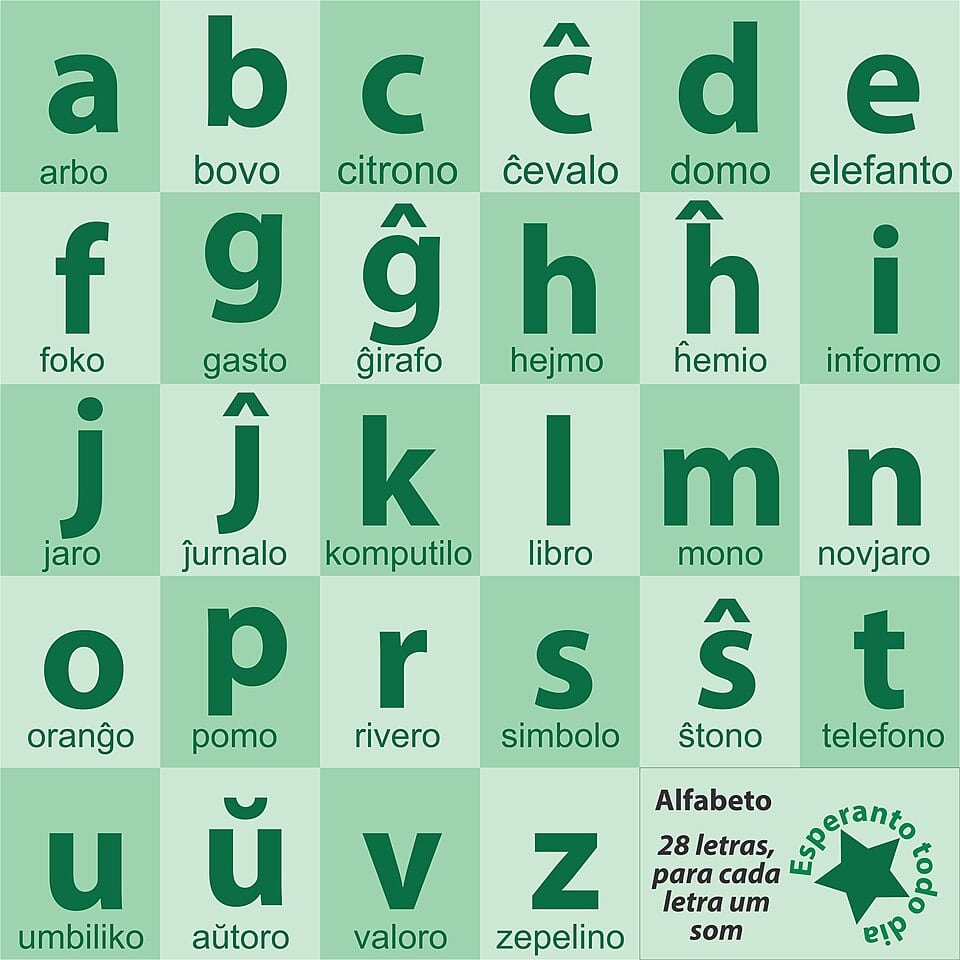

- Consistent endings.

- All nouns end in -o: libro = book, amiko = friend

- All adjectives end in -a: granda = big, bela = beautiful

- Plurals? Just add -j: libroj = books, amikoj = friends

- Direct objects? Add -n: Mi legas libron = I read a book

- Build words like Lego.

Roots + affixes = infinite possibilities.- lern- (learn)

- -ej (place) → lernejo = school

- -ant (person doing) → lernanto = student

- -il (tool) → lernilo = learning tool

- Vocabulary you’ll recognize.

Most words come from European languages (about 75% from Latin/Romance, some Germanic, a bit of Slavic).

Examples:- akvo = water (like aqua)

- patro = father (like padre/pater)

- tri = three (like trois, tres)

Here’s the kicker: studies show you can learn Esperanto in about one-fifth of the time it takes to learn French or Spanish³. And learning it first can even make it easier to learn other languages later.

Why Was Esperanto Created?

Simple. Dr. Zamenhof wanted world peace.

Okay, maybe that sounds corny. But his logic was razor sharp:

- Nations fight because they can’t understand each other.

- Languages give unfair advantages to the powerful (back then French, today English).

- A neutral, shared second language would level the playing field and build trust.

Esperanto was never meant to replace your mother tongue. It was designed as a universal second language—a tool so everyone could talk to everyone, without one culture dominating⁴.

Think of it like this: If you meet someone from China, Brazil, and Germany at a conference, whose language do you use? English. Always English. But that’s not neutral. It gives native speakers an edge. Esperanto wipes that out. Everyone is a learner. Everyone’s equal.

Esperanto and the “Universal European Language” Dream

People love to call Esperanto a “universal European language.” And sure, its vocabulary roots are Euro-heavy. But the vision was bigger. Zamenhof wanted a global tool, not just a European project.

Fun fact: in 1922 the League of Nations almost recommended teaching Esperanto in schools worldwide⁵. France blocked it (surprise, surprise—French elites were worried French would lose its prestige). Later, UNESCO gave Esperanto two official nods, in 1954 and 1985, praising it as a valuable tool for international understanding⁶.

Today, some economists argue the EU should adopt Esperanto to save billions in translation costs and remove English’s unfair dominance. Will it happen? Probably not. But the point is: the idea is still on the table.

Esperanto Language Country: Does It Have One?

Short answer: No. There’s no “Esperanto Nation.” No flag in the UN. No country where kids learn it as their main language.

Instead, Esperanto speakers call their community Esperantujo (“Esperanto-land”). It’s a country without borders, spread across every continent.

Here are some hotspots today:

- Brazil – The biggest Esperanto-speaking community. It’s even tied to Brazil’s Spiritist movement.

- China – Government-backed magazines and radio broadcasts in Esperanto.

- Iran – Strong intellectual circles.

- Togo – One of the most active African Esperanto hubs.

- Hungary – Recognizes Esperanto exams officially in schools.

- USA, France, Germany, Japan – Longstanding, active communities.

There are even native speakers (kids who grow up with Esperanto at home). Probably around 1,000–2,000 worldwide⁷.

So while no passport says “Republic of Esperanto,” the language does have a living, global nation of its own. And thanks to the internet, it’s more connected than ever.

How to Actually Use Esperanto (Without Becoming a Hermit)

Here’s the part people miss: You can actually use Esperanto today.

1. Travel with Pasporta Servo.

Think Couchsurfing, but with Esperantists. Thousands of hosts in 90+ countries open their homes to fellow speakers⁸. Instant travel hack. - PasportaServo.org

2. Read and watch stuff.

Over 25,000 books published in Esperanto. A massive Wikipedia with 375,000+ articles⁹. Music, podcasts, even YouTube channels in Esperanto.

3. Meet people worldwide.

Every summer there’s the World Esperanto Congress. Thousands of attendees from dozens of countries. All chatting in Esperanto. No translators needed.

4. Learn online, fast.

- Duolingo’s free Esperanto course (1.3 million+ learners signed up in just a few years).

- Lernu.net – the OG online Esperanto hub.

- Discord and Reddit communities buzzing daily.

Quick Vocabulary You Can Use Today

Want to impress your friends (or just yourself)? Here’s a mini survival kit:

- Hello = Saluton

- Thank you = Dankon

- Please = Bonvolu

- Yes / No = Jes / Ne

- Cheers! = Je via sano!

- I love you = Mi amas vin

- Let’s go! = Ni iru!

Bonus: wordplay magic.

- From amiko (friend) → amikaro (group of friends) → malamiko (enemy).

- From pensi (to think) → repensi (to rethink) → senpense (thoughtlessly).

See the pattern? Once you learn a few roots and affixes, the whole language opens up like a cheat code.

My Take: Why You Should Care

Here’s the truth: Esperanto will never replace English. That ship has sailed. But that doesn’t mean it’s useless.

In fact, here’s why it’s worth your time:

- It’s a fast win. You can get conversational in a few months. That’s a rush you won’t get from French or Japanese.

- It’s a gateway drug. Learning Esperanto makes other languages easier. Studies prove it.

- It’s a culture hack. You instantly connect with a niche, passionate, global community.

- It’s a statement. By learning it, you’re quietly saying, “I believe communication should be fair.”

So no, Esperanto isn’t dead. It’s the most successful constructed language in history. And if you’re into languages, culture, or just the thrill of doing something different, it’s absolutely worth exploring.

Key Milestones at a Glance

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1887 | Unua Libro published by Zamenhof in Warsaw. |

| 1905 | First World Esperanto Congress, Boulogne-sur-Mer. |

| 1922 | League of Nations debates Esperanto in schools (France blocks it). |

| 1930s | Nazi Germany and Stalin’s USSR ban Esperanto; Esperantists persecuted. |

| 1954 | UNESCO recognizes Esperanto’s cultural value. |

| 1985 | UNESCO encourages teaching Esperanto in schools. |

| 2012 | Google Translate adds Esperanto. |

| 2015 | Duolingo launches Esperanto course; 1M+ learners sign up. |

Sources

- Zamenhof, L. L. Unua Libro (1887). Wikisource: Dr. Esperanto’s International Language

- Declaration of Boulogne (1905). Wikisource: Boulogne Declaration

- Helmar Frank, “The Propaedeutic Value of Esperanto.” (Interlinguistics, 1970s). Wikipedia: Paderborn method

- Zamenhof’s introduction to Unua Libro. Wikisource: Dr. Esperanto’s International Language

- League of Nations archives, Geneva, 1922. Internet Archive: Esperanto as an International Auxiliary Language

- UNESCO Montevideo Resolution (1954); Sofia Resolution (1985). UNESCO Archives

- Nielsen, Svend. “How many people speak Esperanto?” (2017). Svend Nielsen’s Blog

- Pasporta Servo network, official website. pasportaservo.org

- Esperanto Wikipedia statistics, Wikimedia Foundation, 2025. Esperanto Wikipedia